“Kids are hard to kill,” our firstborn’s pediatrician said to me during a panicked phone call from Puerto Vallarta. Connor was eight months old and Ed and I were taking our first real vacation – with the baby, of course – since he’d been born.

Granted, we found out later that our doctor’s staff had looked up flights to Mexico if things went bad, but his words were incredibly comforting and prophetically true, when looked at through the lens of all the other parenting nightmare stories we heard when we told ours.

Walking around Puerto Vallarta had always been one of our favorite things to do – from our first photo safari “date” through our wedding at our favorite P.V. restaurant two years prior. And we’d worn Connor in a sling or a carrier since he was a newborn, which made everything from travel to cleaning the house as easy as it got with a baby. When Ed carried him in the front-facing Baby Bjorn, women came out from shops to squeeze the chubby baby thighs and tickle his rolls with delight. Connor was a baby who never cried, was an easy sleeper (in our bed) and he traveled without complaint, so strangers coming to say hello inspired an infectious gummy grin.

The day we thought we’d killed him, we’d spent a couple of hours walking around the old part of town, looking in shops to see what had changed since we were last there. We were headed home to our family’s condo, and were walking up the worn brick steps we’d traveled hundreds of times over the many years we’d visited when Ed’s Teva sandal caught on an uneven brick and he fell forward. All he could think of to do was catch himself so he didn’t crush the baby he wore on his chest, but he didn’t calculate the extra slack of the Baby Bjorn into his equation.

The sound of your baby’s head hitting the bricks is not one from which you ever recover, and during the horrifying moment of silence before the bloodcurdling scream of pain, Ed was convinced he had just killed our child.

It’s a silence neither of us ever wants to experience again in our lives.

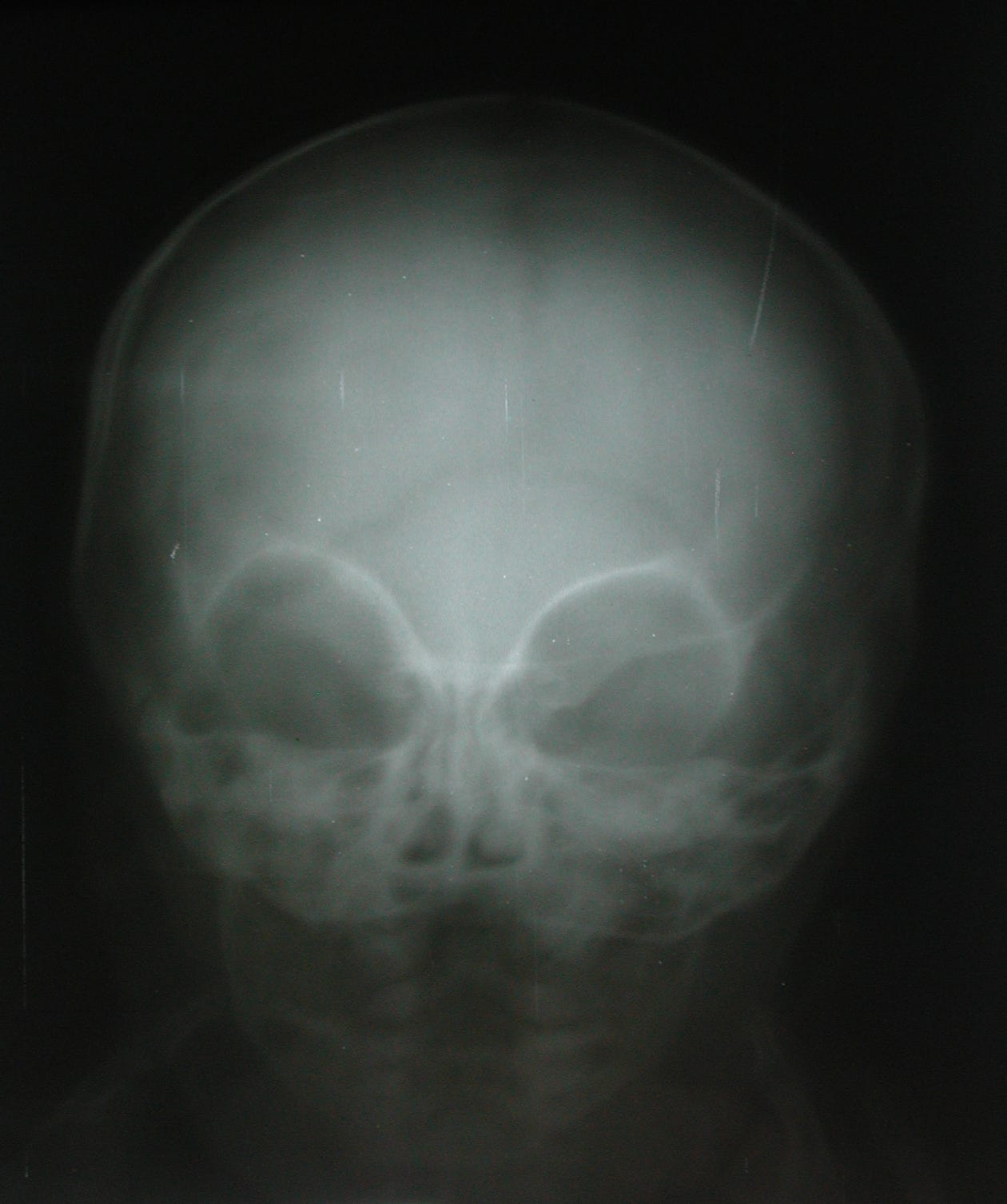

I was actually grateful for the unrelenting scream as we raced to the tiny medical clinic nearby, where the tech put our baby in a pre-war X-ray machine to image his skull. After the traumatic X-ray, I rushed him home to our condo to call the doctor while Ed stayed behind to photograph the images on the lightboard with his digital camera

.While I frantically dialed the phone, Connor’s screams of pain and shock finally quieted enough that he could latch on and nurse, and during that first call, his doctor calmly explained that baby skulls were pliable in the way cartilage was, and the fact that he was so young gave him a distinct advantage in surviving the game of life.

I’d finally gotten Connor to sleep when Ed arrived home to email the digital images of our baby’s skull to our doctor in California, and he was the one to hear the relieved “he’s fine” from him when he called back. “He’ll have a headache for the next few days, but no lasting damage.”

We visited with friends the next night – other parents whose kids were in little league and gymnastics, and had stayed home with grandparents while their parents vacationed in Mexico. We shared our terrifying day, and there were so many sympathetic nods and noises, with stories of near misses, bloody heads, and broken bones that we felt seen and understood and not judged.

Each story taught a lesson that everyone had their own terrifying day with their child, and the lessons we can impart to others from that awful accident were:

1. You can’t see your feet when you wear your baby in a front pack. Choose your footwear accordingly.

2. Anticipate the slack in a baby carrier if/when you fall.

3. If there’s an X-ray, take digital photos for instant messaging to pediatricians.

4. Afterwards, tell your story. You’ll find understanding, sympathy, and things to learn from other parents’ stories of their own nightmares.

5. Babies are resilient and trusting, they don’t hold grudges, and they’re thankfully hard to kill.

My second child had a habit of fainting after sudden, stressful moments. Well, it had happened twice before this story but it felt like a habit. It was terrifying and I was all set to take him to the pediatrician in a few days to make sure everything was ok. I loved 3 out of 4 of the pediatricians in the practice. I assumed I would love the 4th, I’d just never met her. She was on call the day that my son fell out of his crib where I had put him so I could have two minutes, three tops, of privacy in the bathroom. The side of the crib wasn’t latched all the way even though I would swear I heard the click. Anyway, he fell, I dashed off the toilet in that way parents do, picked him up and he fainted. It was awful to see. He came to, I was a mess, I called the pediatrician and got Dr. #4. I told her what happened, explained that this wasn’t the first time my toddler had fainted, and I can’t tell you her exact words but I got off the phone feeling like my kids were in danger and I was an unfit mother. It may have been a worse feeling than watching my kid faint.

Turns out, as I was told by a pediatric neurologist, some kids are fainters. There’s a fancy name for it, as the doctor told me “we used to just call them fainters and he’ll most likely grow out of it by the time he’s 4 years old or so.” And in the meantime there was an easy fix. When he was suddenly scared and in shock he would forget to breathe. The fainting was his body’s defense mechanism to get him to breathe automatically again. To keep him from fainting we had to get him annoyed enough to forget he was scared. I was told by the doctor that when my son was upset but not making any noise and not breathing to whack him on his bottom a few times, not too hard but enough to get him annoyed. He would be too angry to stay in that shocked mode. I got some weird looks in the playground but it worked!

Long story long, of course, I wish Dr. #4 had said something like “kids are hard to kill” and I’m so glad your trip to Mexico ended happily.